According to Coco Chanel (1883-1971), the silhouette of flapper fashion was born more of chance than design. She told us: “One day in Deauville, I put on a man’s sweater because I was cold. I tied it with a handkerchief at the waist. Fellow vacationers asked, “Where did you get that dress?” I responded, “If you like it, I will sell it to you.” Ten dresses later, the signature Chanel frock was born. This scenario describes just how fashion trends begin.

After that, Chanel seized the opportunity to design for this new adventurous woman whose day combined work, sport, and leisure. She began to blur the lines

between masculine and feminine, and between costume and real jewelry. Recognizing the evolution from Victorian Society to a more streamlined Modernism, Chanel began to do a brisk business in navy blue blazers, turtleneck sweaters and other loose-fitting garments she created out of knit, flannel, and the new sexy rayon material that no other dressmaker had ever dared to use. Her main objective was to make every women feel comfortable and attractive.

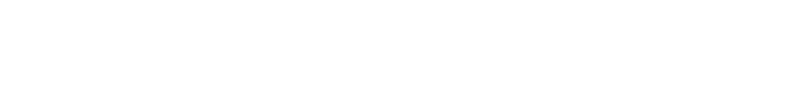

Chanel opened her Paris fashion house in 1921 at the very start of the Jazz Age. The most familiar ingredient of her flapper fashion was the shortened hemline with skirts that were fourteen inches above the ground. The New York Times reported from the French fashion shows: “Display of Spring fashions shows them barely long enough to cover their knees.” Women bobbed their hair short and began to wear skirts in which they could jump onto a bus easily, or even better, do the Charleston. Chanel’s innovation of the little black dress has been called “the Ford of Fashion.” Everybody had one (and most women still do)! This trend scandalized defenders of the old order who were alarmed at the sight of bare legs. Silk stockings, created by Pierre Poiret, became a feature of the look. Many took the “New Woman” in stride – and even the conservative Ladies’ Home Journal wrote, “…American women are now noted for their pretty feet and ankles. It is pleasant to

know that skirts are going to be short…though one must adjust length to becomingness.”

Coco Chanel encouraged women to use what they already owned in clothing and accessories, but she encouraged them to add modern touches to their outfits like a brightly colored scarf, a handsome hat, an attention-getting brooch, or fantastic footwear.

When I was a student studying design at Pratt Institute, I would to go to the old Metropolitan Opera House and sketch the subscribers as they arrived for opening night. The parade of society ladies was a feast for the eyes in color, fabrics, and shape with each diva attempting to outdo all the others. How delicious it was to see this panoply of extravagance and consumerism! There will never be its equal.

In my career as a designer, I embraced Chanel’s ideas in order to make my own creations timely. I always attempted to bring a new look into my work – but not an extreme one. The women who bought my clothes wanted to look attractive – not weird. I think back in pleasure at how Chanel, my muse, influenced my thinking and my love of French Couture. Coco Chanel was High Fashion herself!

Terryl Lawrence, Ed.D., earned her doctoral degree in art and education from Columbia University and has had many exhibitions of her paintings and photographs in New York and Florida. She has written several published articles, was a New York fashion designer and photographer and wrote the preface to Chaim Potok’s “Artist in Exile,” has taught photography and art at C.W. Post College and SUNY Empire State College. She is an NEH Fellow in the Humanities. Professor Lawrence currently teaches Art History and Mythology at Palm Beach State and Broward Colleges.